Learn how to prevent the condition that has led to tragic consequences for mountaineers during one of Mount Everest’s most treacherous seasons.

TEXT & INFOGRAPHIC: EVELINE GAN

PHOTO: FLICKR USER SCILLA KIM

In May, a Singaporean climber went missing after reaching the summit of Mount Everest. He was reportedly suffering from frostbite and altitude sickness when he got separated from his group. The news, which came amid a spike in fatalities on the world’s highest mountain, raised questions over whether a rising number of inexperienced climbers and guides led to this. What’s certain, is that another factor partially responsible for many of the deaths that occurred this year is altitude sickness.

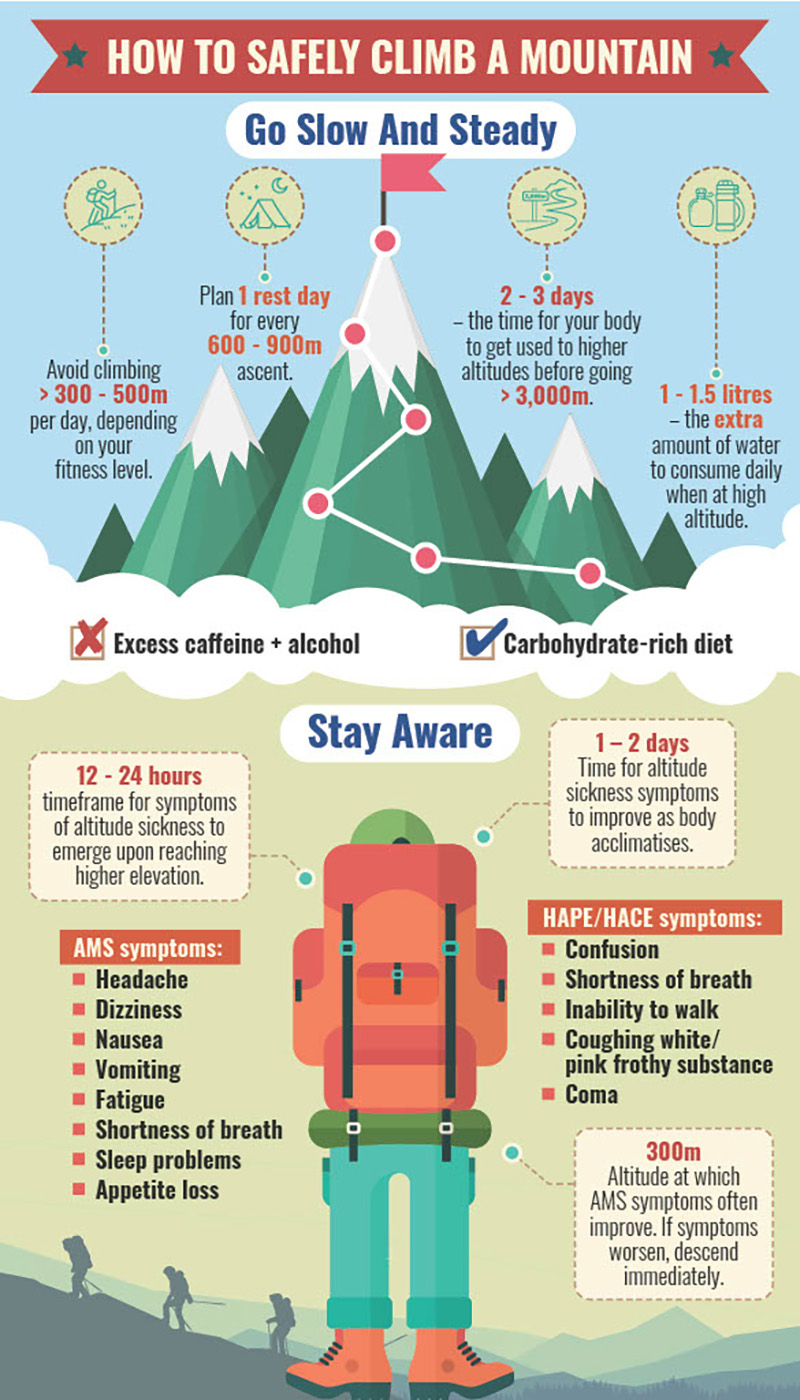

According to American academic medical centre Cleveland Clinic, altitude sickness may occur in up to half of people who climb to elevations above 8,000 feet (2,440m). It is caused by ascending too rapidly, which doesn’t allow the body sufficient time to adjust to reduced oxygen and changes in air pressure.

Don’t ignore the signs

As mountain climbing becomes increasingly popular, being aware of the risks and red flags of altitude illnesses is key to a safe experience. The mildest form of altitude sickness — which can usually be treated by over-the-counter medication — is known as Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), with symptoms that recall a hangover. This can deteriorate into High-altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), a life-threatening build-up of fluid in the lungs, and High-altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), a severe condition where there’s fluid in the brain. Such cases require immediate medical attention.

Regardless of your climbing expertise, all high-altitude adventures come at a risk of potentially life-threatening altitude sickness, points out Mr Vijay Kumar, director of SGTrek, an outdoor travel platform that offers mountaineering expeditions. “Even experienced climbers may fall victim to altitude sickness if they disregard proper acclimatisation practices or ignore their body’s warning signals,” he explains.

With that being said, individuals at higher risk of developing altitude sickness include those with lung or heart conditions, pregnant women and climbers who live at low elevation — such as in Singapore.

Mr Vijay adds that in some cases, climbers may benefit from using medication like acetazolamide (Diamox) to prevent and reduce the symptoms of altitude sickness. However, it is important to discuss this option with a medical professional before use.

Never underestimate the mountain and its challenges, Mr Vijay cautions, adding that “the key to preventing altitude sickness is a gradual ascent, allowing the body to acclimatise to higher altitudes”. “Listen to your body and be aware of any symptoms of altitude sickness. If conditions or circumstances become unsafe, be prepared to turn back. The mountain will aways be there and your safety should be top priority,” he emphasises. It is also important for people with medical conditions to obtain a doctor’s clearance before embarking on a high-altitude hike.

Being physically and mentally prepared, and taking the necessary precautions during ascent can reduce your risk of developing altitude sickness. Here are more tips for ensuring a safer and enjoyable climb.

Like our stories? Subscribe to our Frontline Digital newsletters now! Simply download the HomeTeamNS Mobile App and update your communication preference to ‘Receive Digital Frontline Magazine’, through the App Settings.